Programs often have secrets that their programmers want to hide, and it is not always possible to just store them server side. Whether you’re Snapchat hiding the algorithm to generate request tokens, Widevine hiding a private key used for DRM, or Google hiding the signals ReCaptcha collects to determine whether you’re a human or not, obfuscating client software is a common and often necessary practice. This article will discuss some of the techniques used to obfuscate software.

Compile Time Obfuscations

These types of obfuscations are usually performed at compile time using LLVM transformation passes that work on LLVM intermediate representation code. Obfuscator-LLVM implements many of these.

MBA

| MBA expressions, or mixed-boolean arithmetic expressions, are expressions that contain bitwise logic (&, | , ^, », «) and regular arithmetic operators (+, -, *). These expressions can be used to represent constants or binary operators. For instance, we can replace x + y with (x ^ y) + 2*(x & y). (x & ~y & ~z | x & ~y & z | x & y & ~z | x & y & z) - (~x & ~y & ~z | x & ~y & ~z | x & ~y & z | x & y & ~z | x & y & z) + (~x & ~y & ~z) will evaluate to 0 regardless of the values of x, y, and z. (((x - ((x ^ 0xffffffff | 0xffffff3f) & (y ^ 0xffffffff))) - y) + (y & x | ((x ^ 0xffffffff) & y) & 0xffffff3f | ((x ^ 0xffffffff | 0xffffff3f) & (y ^ 0xffffffff)) | ((x ^ 0xffffffff) & y) & 0xc0) & y) is equivalent to x & y for 32 bit integers. Wrap your head around that one. Aside from making it very difficult to discern what the code is doing, this obfuscation also has the advantage of slowing down symbolic analyzers like Manticore or Angr. For instance, this expression was found inside of a Snapchat binary: |

((((((((0x431e33362537db49 | (~((~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c ^ ((0xbac03a4c7e26a10c & (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | (bss_val1 & (~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c) & 0xffffffffffffffff)))) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xc92460b4173d8ad1) | ((~((0x431e33362537db49 | (~((~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c ^ ((0xbac03a4c7e26a10c & (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | (bss_val1 & (~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c) & 0xffffffffffffffff)))) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff))) & 0xffffffffffffffff) & (~(0xc92460b4173d8ad1) & 0xffffffffffffffff))) ^ ((0xc92460b4173d8ad1 & (~((((0x431e33362537db4a | (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) - (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | ((((0x431e33362537db4a | (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) - (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff) & (~(0xc92460b4173d8ad1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)))) | (~(((0x431e33362537db49 | (~((~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c ^ ((0xbac03a4c7e26a10c & (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | (bss_val1 & (~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c) & 0xffffffffffffffff)))) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | (~((((0x431e33362537db4a | (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) - (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff))) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | 0x253a41858a5c76d6) - ((((((0x431e33362537db49 | (~((~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c ^ ((0xbac03a4c7e26a10c & (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | (bss_val1 & (~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c) & 0xffffffffffffffff)))) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xc92460b4173d8ad1) | ((~((0x431e33362537db49 | (~((~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c ^ ((0xbac03a4c7e26a10c & (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | (bss_val1 & (~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c) & 0xffffffffffffffff)))) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff))) & 0xffffffffffffffff) & (~(0xc92460b4173d8ad1) & 0xffffffffffffffff))) ^ ((0xc92460b4173d8ad1 & (~((((0x431e33362537db4a | (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) - (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | ((((0x431e33362537db4a | (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) - (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff) & (~(0xc92460b4173d8ad1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)))) | (~(((0x431e33362537db49 | (~((~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c ^ ((0xbac03a4c7e26a10c & (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | (bss_val1 & (~(0xbac03a4c7e26a10c) & 0xffffffffffffffff)))) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) | (~((((0x431e33362537db4a | (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) - (~(bss_val1) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0xffffffffffffffff))) & 0xffffffffffffffff)) & 0x253a41858a5c76d6)) & 0xffffffffffffffff)

Most simplification libraries will not produce useful output for this expression. Arybo is probably the only one that would. There are algorithms involving some simple matrix math that can generate an infinite number of these expressions. I wrote some code to generate these expressions that always evaluate to 0 as part of an LLVM obfuscation pass I am working on. Ninon Eyrolles’ doctoral thesis is probably the best introduction to this topic and this paper from Cloakware researchers in 2007 is also very good. For some common MBA substitutions, see the appendix.

Opaque Predicates

The term “opaque predictate” usually refers to an expression that always evaluates to true or false that is known at a compile time but are evaluated at run time. Imagine if we had the following code:

int x = 5;

x = 1 << x;

x = 2*x + 9;

// more complex calculations...

We could instead say:

int x = 5;

if (x % 2) { // 5 does not evenly divide by 2 so this is always true

x = 1 << x;

x = 2*x + 9;

// more complex calculations...

}

Or:

int x = 5;

if (((4*x*x + 4) % 19) != 0) { // (4x^2 + 4) % 19 != 0 for all integers

x = 1 << x;

x = 2*x + 9;

// more complex calculations...

}

Or, combining the above two examples (also including misleading else statements):

int x = 5;

if (((4*x*x + 4) % 19) != 0) { // (4x^2 + 4) % 19 != 0 for all integers

if (x % 2) {

x = 1 << x;

x = 2*x + 9;

// more complex calculations...

} else {

x *= 5;

}

} else {

x += 95;

}

This can result in the control flow graph becoming significantly more complicated, again making your program harder to understand. The above section on MBA expressions might be useful here because it is possible generate expressions that appear to performing some kind of calculation but actually always evaluate to a constant. This paper is a good introduction to this topic and includes discussion on more advanced kinds of opaque predicates.

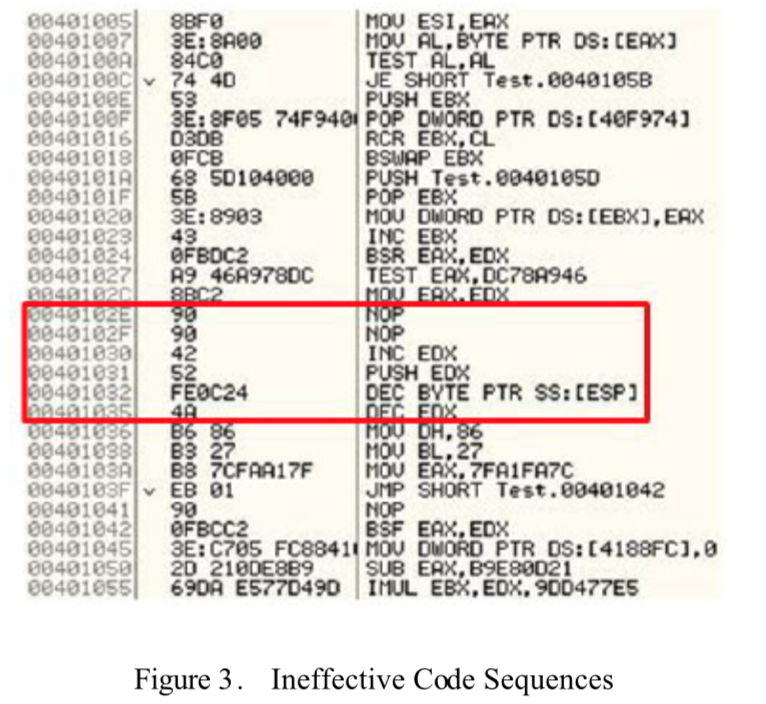

Junk/Dead/Garbage Code Insertion

“Junk code” is useless code that does not affect the functionality of the program. It is often used by malware to evade signature detection.

For instance, this code from a botnet

makes Windows API calls but does not use the result in any way. There are simpler ways too, like adding assembly instructions that don’t do anything:

.

.

Obfuscator-LLVM implements this as part of their bogus control flow component. Essentially, for every block of code, they replace it with an if statement (branch instruction) with an opaque predicate that is always true, then put everything that was formerly in the block under that if statement along with randomly generated arithmetic instructions.

Control Flow Flattening

Control flow flattening will make your code look like:

Control flow flattening usually involves a giant switch statement that controls the state telling the program what to next. For instance imagine we had the following code:

i = 1;

s = 0;

while (i <= 100) {

s += i;

i++;

}

This could be flattened like so (this is the “switch dispatch”, there are other methods involving goto and function pointers):

int next = 1;

while (next != 0) {

switch (next) {

case 1:

i = 1;

s = 0;

next = 2;

break;

case 2:

if (i <= 100) {

next = 3;

} else {

next = 0;

}

break;

case 3:

s += i;

i++;

next = 2;

break;

}

}

Obviously this can be tricky to implement and is probably the most likely to cause code breakage among all the obfuscations covered so far. We can make this even more difficult to understand by replacing the keys for the switch statement (1, 2, and 3) with random numbers (although when generating random numbers it would be necessary to make sure they are unique).

Packing

This is especially common in malware. Usually, a packer is a program that runs on an already compiled binary, compresses it, and turns it into an executable that will decompress itself at runtime. This hides strings in the binary and makes reversing the compressed binary difficult. UPX is one such packer.

For instance, if we run it on /bin/ls:

$ upx /bin/ls -o ls

Ultimate Packer for eXecutables

Copyright (C) 1996 - 2018

UPX 3.95 Markus Oberhumer, Laszlo Molnar & John Reiser Aug 26th 2018

File size Ratio Format Name

-------------------- ------ ----------- -----------

138856 -> 61540 44.32% linux/amd64 ls

Packed 1 file.

We can unpack it with upx -d ./ls. Because of UPX’s ease of unpacking, it has become common to use a modified version of UPX to make unpacking more difficult. “Modding” UPX merely requires changing some constants. If you change the UPX magic numbers, standard UPX will not recognize the packed files as UPX files. It is also possible to modify the value of fields like p_filesize in the UPX header so that the upx command will fail. This forces analysts to get the debugger out to unpack the binary.

Virtualization

VMProtect is famous for doing this. This is also becoming common increasingly common in Javascript antibot scripts. Essentially, “virtualization” refers to the process of transforming all the instructions in a program into a custom set of instructions and implementing an emulator that is able to understand these instructions. One example I found of this was an antibot script on nike.com. I am using a Javascript example here because it is easier to understand than assembly.

We can first see that they are passing a giant text blob as an argument to a function. This is the bytecode, base64 encoded (it goes on for another 240k characters).  .

.

Now we can see the function that actually executes the instructions:

The variable names makes it difficult to understand but essentially it is iterating over all the instructions in the (at this point decoded) bytecode and executing them. We can see it is getting values from the c array, which is really just a list of instructions containing operations in Javascript:

This makes reverse engineering significantly more difficult because it requires analysts to figure out your new instruction set and transform it into a form they/their tools can actually understand.

Conclusion

There are many ways to obfuscate a program. Ideally, only sensitive code should be obfuscated to avoid performance problems. Obfuscation techniques should be selected in a way that maximizes confusion to analysts while minimizing adverse performance impacts. There are other obfuscation techniques not covered here that I may cover a later date, including white box cryptography and string obfuscation (typically using XOR/RC4).

Appendix: Common MBA Substitutions

* (x + y) == ((x ^ y) + 2*(x & y))

* (x + y) == ((x ^ y) - ((-2*x - 1) | (-2*y - 1)) -1)

* (x + y) == (2*(x | y) - (~x & y) - (x & ~y))

* (x + y) == ((x | y) + (x & y))

* (x + y) == (~(~(x + y) | ~(x + y)) | ~(~(x + y) |~(x + y)))

* (x - y) == (x + ((y^-1) + 1))

* (x - y) == ((x ^ (~y+1)) - ((-2*x - 1) | (2*y - 1)) - 1)

* (x - y) == ((x & ~y) - (~x & y))

* (x - y) == ~(~x + y)

* (x ^ y) == ((x | y) - (x & y))

* (x ^ y) == (x + y - 2*(x & y))

* (x | y) == ((x ^ y) ^ (x & y))

* (x | y) == (x + y - (x & y))

* (x & y) == (~(~x | ~y))

* (x & y) == (x + y - (x | y))

* (x & y) == ((x | y) - (~x & y) - (x & ~y))